John Glasgow, Program Director, Association of Illinois Rural and Small Schools

David Ardrey, Executive Director, Association of Illinois Rural and Small Schools

Tom Withee, Director, Goshen Consulting Inc.

A healthy public school system is essential for a vibrant society and a robust economy. These institutions are a cornerstone of American life. Challenges in how we conduct education, how we inspire young people to join the profession, as well as an enduring negative narrative about the value of the system have resulted in an intense shortage of certified educators. While some strides have been made in addressing the shortage, it remains persistent and pervasive. Rural schools are disproportionately affected by this shortage. The challenge at hand is to understand where and how this educator shortage manifests in rural schools, and what steps we can take in collaboration to begin addressing it.

The Association of Illinois Rural and Small Schools (AIRSS) stands as the voice for all rural districts in the state through advocacy and leadership at all levels from local to national [1]. The chronic shortage of teachers, support staff, and administrators in rural schools is a core concern for the organization. AIRSS has worked to tackle the shortage through the newly created Rural Education Advisory Council at the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE), through research and policy action as an affiliate of the National Rural Education Association, and through collaborative efforts across Illinois. This white paper reviews the work of the ISBE and the Illinois Association of Regional Superintendents of Schools (IARSS) Educator Shortage Report: Academic Year 2024 – 2025, to reveal what their findings say about the shortage in rural districts and how to address it.

While the newest data appears hopeful, with no significant increase in unfilled positions, this year-to-year stability does not necessarily constitute the end of the educator shortage in rural Illinois. Most Illinois school districts still harbor a shortage, and rural districts are more likely to have both a shortage and difficulty finding lasting solutions.

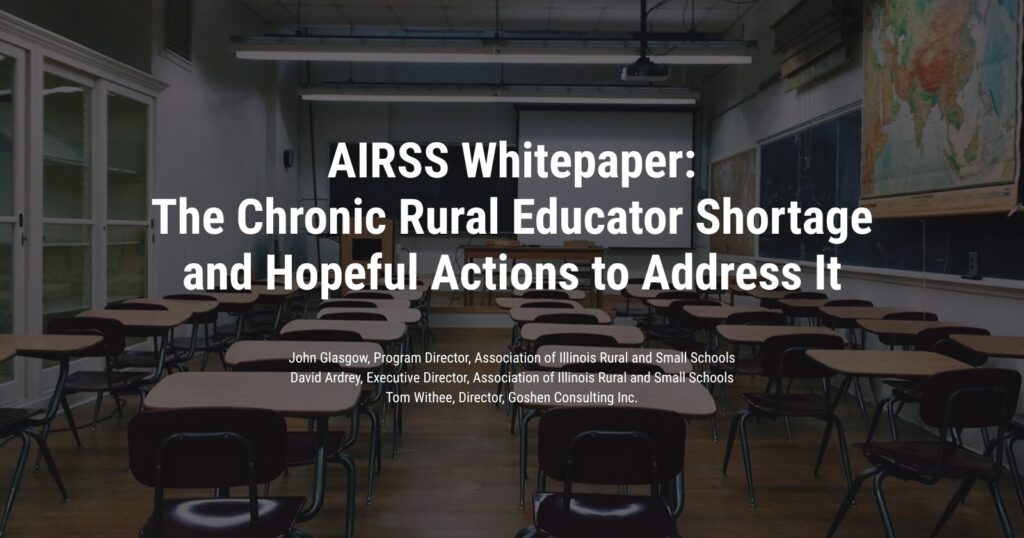

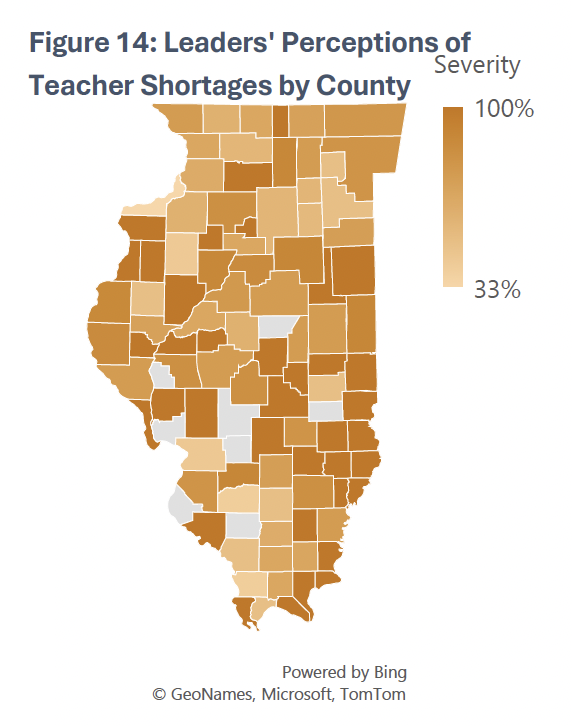

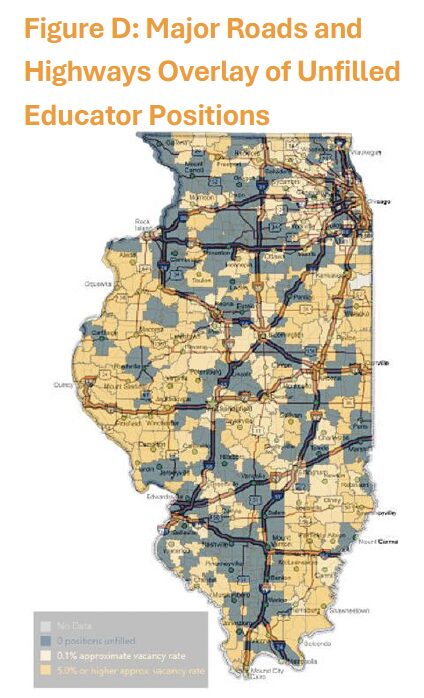

The overall map of unfilled teaching positions from the report (Figure 2) reveals that some of the most rural and remote regions of the state (west central, east central, and southeast) are those with the most unfilled positions. Moreover, the severity of those shortages is more pronounced, as seen in Figure 14 from the report shown below. While non-rural districts also experience shortages, there are meaningful differences in the results gathered from rural districts that offer deeper insights. In reviewing the report, AIRSS has found four key points to elevate for understanding and tackling the rural educator shortage.

Shortages Hit Rural Districts Harder

The lack or loss of a single educator, staff person, or administrator in a small school district has an outsized impact on the quality and capacity of the district. These gaps are most visible in limited course offerings and learning opportunities as well as the reduced operational capacity of the district. It is often said that working in a rural district means “putting on many hats,” and while this is a benefit to educators looking to be more autonomous and innovative in their profession, it is still a sober reminder that our existing rural education workforce must go to extreme lengths to cover basic services.

Beyond the quality and quantity of educational content, shortages in rural districts also come with immense sunk costs that are disproportionately harmful to them. It costs real time and finances to recruit, train, and weave a new hire into a rural community. When that person invariably leaves, the district loses those scarce resources. While a larger, better-resourced district can work around the sudden departure of a new hire, it is difficult for rural districts to continually absorb these costs. This further impacts the breadth and depth of their offerings. Figure 14 above illustrates a higher severity of shortages for rural districts which emphasizes both phenomena.

There is a Crisis of Quality

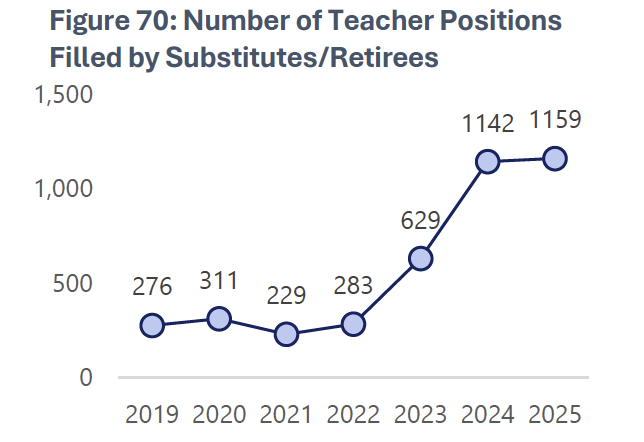

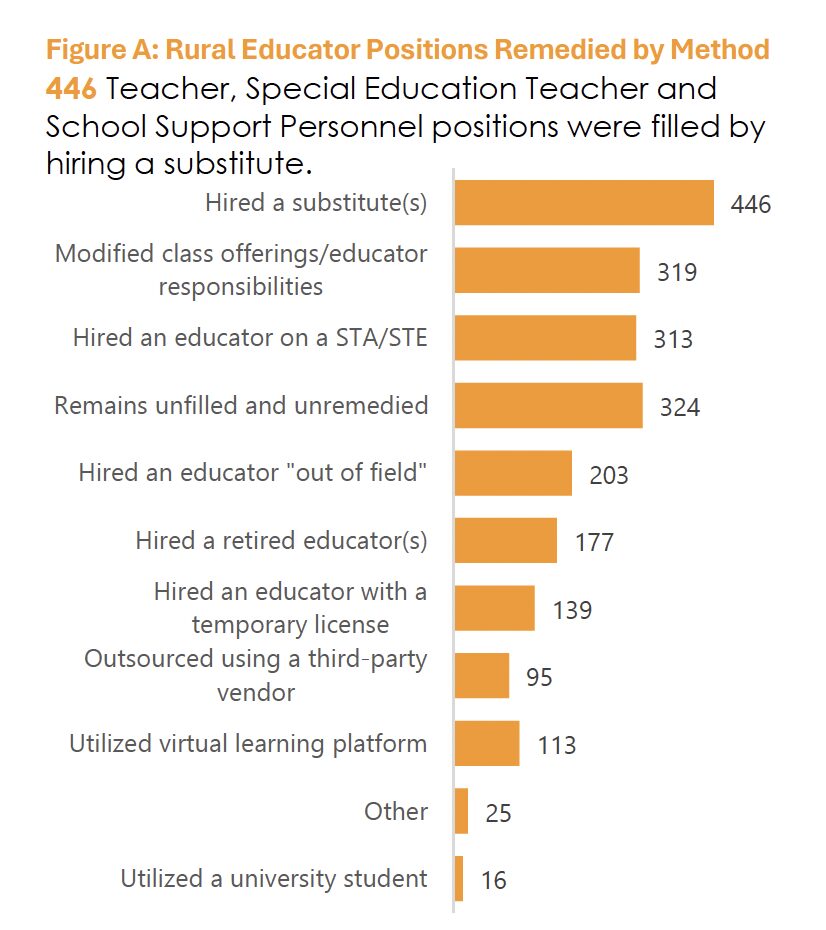

The report also raises a serious question about the quality of personnel being hired to fill chronically vacant positions. District leaders act with best intentions to ensure that students can receive the opportunities and services they need to succeed. This often means bringing on partially or non-certified staff to fill open positions. Figure 70 from the report shows this point clearly. Since 2022, the number of teaching positions filled by substitutes or retirees has ballooned by 400%. Digging even further through the accompanying dashboard reveals that hiring a substitute teacher is the most common alternative method used to remedy unfilled positions (see Figure A). For rural districts, hiring a substitute accounted for 446 of the 2170 positions filled by other means in rural districts. In total, over half of all vacant positions filled in rural districts (1101 out of 2170) were filled by hiring a substitute, an educator with a temporary or short-term license, or even hiring someone outside of the field entirely. In fact, in the report reveal that only 43% of teaching applicants and 53% of special education applicants were considered “qualified” by district leaders.

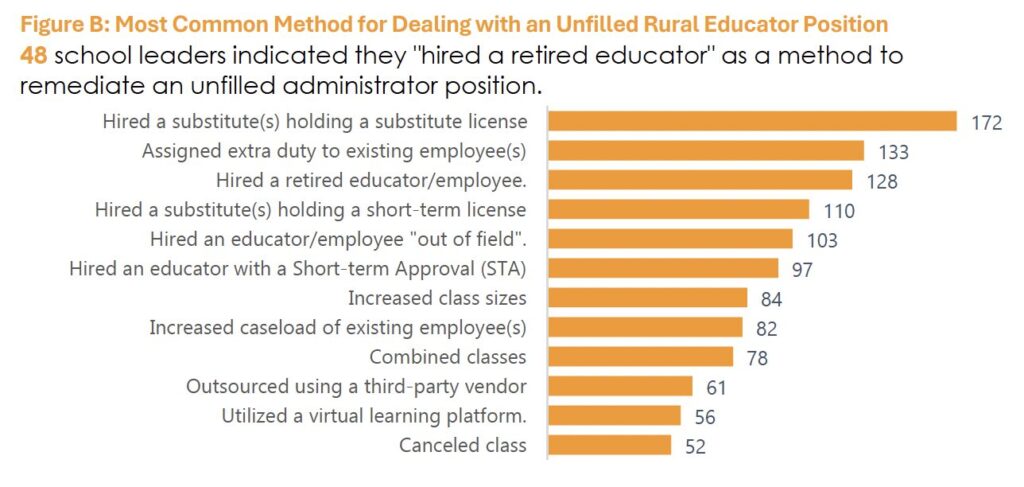

The crisis of quality also highlights the risks of overtaxing existing educator and staff capacity. The dashboard identified assigning extra duties to existing staff was the second most common strategy rural districts employed to cover unfilled positions (see Figure B). Rural educators pride themselves on “wearing many hats,” but the painful reality is that adding this additional burden to existing staff increases teacher burnout, lowers long-term retention, and perpetuates negative perceptions of teachers as overworked for little reward. An overworked teaching staff contributes to the reduced depth and breadth of school offerings and opportunities as much as uncertified staff; and this is seen most prevalently with rural special educators.

The Problem Begins with Teacher Recruitment

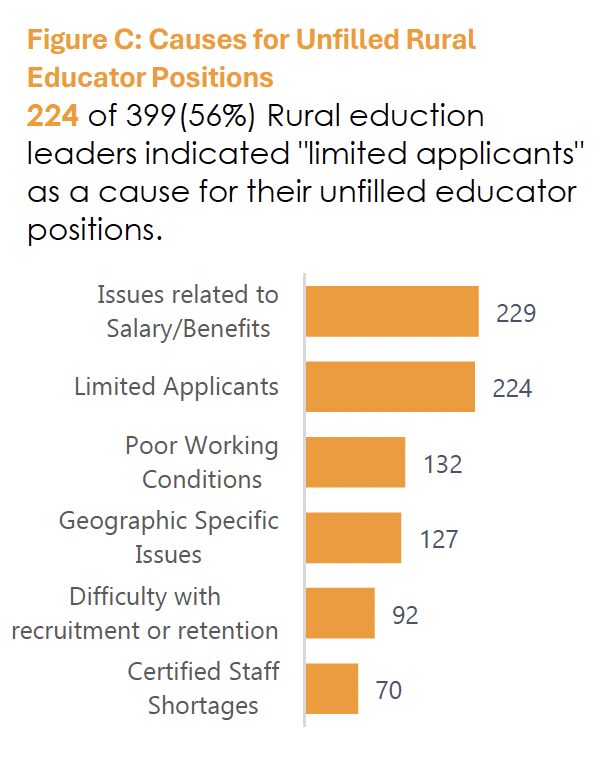

The inability to recruit talent into the education profession that contributes most substantially to the ongoing educator shortage. It is unsurprising that “limited applicants” is a leading cause and impact of educator shortages for rural districts (see Figure C). Discussion program in high school, at a local community college, or at a four-year institution, most entrants to the profession face the prospect of years of student debt, up to five years in college for minimum licensing, and the uncertainty of passing state certification exams. Along with this, there is the overwhelmingly negative external narrative surrounding the profession from a charged social and political environment. All of this means that aspiring educators are often cut short before they even begin, and that truly new and innovative ways of supporting them through the process and into the profession are essential.

There are a growing number of robust para-to-pro programs that provide a quicker entry point to the profession while also earning an income and making use of existing work experience. Other successful alternatives to educator preparation rely on rooting the program experience in local needs and unique attributes. Still others go to lengths to help students earn clinical experience as early as they can and find numerous ways to fund their continuing education. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to how we can better recruit, train, and retain our educators, but our solutions must help students enter the field quicker, cheaper, and earlier without sacrificing quality, and all the while being immersed in an asset-minded and place-based approach to the profession.

Geography is a Primary Challenge without a Strong Solution

Overall, the results of the report reveal a broad alignment between rural and non-rural districts on the causes of and solutions to the educator shortage. Yet, this by no means suggests that a standard approach would be equally effective for both. There is a single key difference that has great consequences for our entire approach to addressing rural shortages: geography. The difference here is stark. From the online dashboard, 127 rural district leaders indicated that “geographic specific issues” were a cause of their shortages, compared to just 13 non-rural district leaders who indicated the same. The “rural experience” in large part is a story of grappling with geography, and while many who call small towns and country places home adapt to the realities of where they live, these realities are still a major influence on a district’s ability to attract and retain staff.

At the most basic level, the problem with geography is physical access. It is simply hard to get to some of the most in-need districts and equally hard to attract qualified staff not originally from that area. In fact, there is a direct correlation between easy access to major highways and transportation hubs and the educator shortage, as seen in Figure D. This map reveals that the closer a district is to a major highway, the more likely they are to fill vacant positions. It is easier to get to these districts and to access services and opportunities when major thoroughfares provide a direct line of physical connection to the larger world.

On a deeper level, the physical remoteness of a district and their difficulty in filling vacant positions is also related to the ability of the larger community to attract and retain new residents. For the exact same reasons, rural communities without quick, direct access to major roads and transportation hubs find it more difficult to attract economic opportunities, consumer services, and social services. Even though this typically means that real estate and consumer good prices are generally lower, so too are income rates. In this environment, school districts struggle to offer a competitive salary, and they have little external opportunities for partnership to enhance their offerings to staff and students.

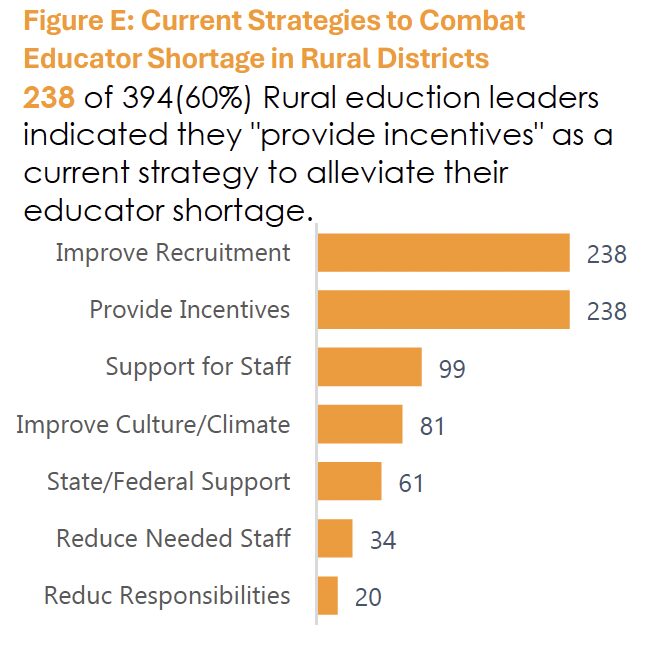

Both of these factors are seen in the report data. Rural district leaders indicated that issues related to salaries and benefits are the second most prevalent cause of the shortage, and that providing additional incentives is tied as the most prevalent solution and is the second most desired solution to the problem behind increased state and federal support (Figure E).

However, the problem with geography is that we do not have a good way of managing it. We lack a strong means for managing the distance to services and opportunities, and we lack an effective message for showing geography as an asset rather than a barrier. Even for those born and raised in a rural place, cultivating a sense of purpose and belonging can still be a significant challenge in an area that is remote and small. Although rural schools are often stereotyped as better, more community-based places to work, we lack a clear “playbook” for introducing educators to the realities of living and working rurally. This in part might explain why “poor working conditions” were listed as the third most common cause for the educator shortage in rural districts (see Figure C above).

Our lack of a strong local approach to managing geography lastly extends upwards into state government. Illinois state policies and curriculum tend to be geography-blind, and so they disproportionately harm rural districts. State funding mechanisms do not account for the smaller, more remote reality of many districts. As a result, they tend to be chronically under resourced while being expected to perform at the safe capacity as larger, non-rural districts [2]. Moreover, curriculum without context does not accurately reflect the lived reality of students, nor provides them with the opportunity to utilize local assets to advance academic and career education. This discourages students from investing locally and does not inspire them to return as a future educator or to espouse the benefits, assets, and opportunities of newcomers moving to a rural district [3].

Looking Ahead: Signs of Hope & Areas for Action

The educator shortage in Illinois persists. This challenge severely limits the ability of our public education system to function as the cornerstone of our society and economy, and it is most prominently observed in rural school districts. Nevertheless, there is reason to have sincere hope that change is possible and that data-driven solutions can have an impact. The Association of Illinois Rural and Small Schools works with partners at the local, state, and national levels to find effective answers to the rural educator shortage. Although some issues like teacher salaries and benefits, curriculum mandates, and rural representation in policy will require time, other areas for action can be taken here and now to have a direct impact on the ability of our schools to find and keep high-quality, certificated teachers, staff, and administrators:

First, there needs to be a more committed effort to rethinking educator preparation. K12 schools, higher education institutions, state agencies, and local community partners need to come together at the same table to review successful models, talk through institutional barriers to innovation, and adapt local solutions to inspiring, training, and retaining or attracting educators. This must include opportunities to become an educator faster and cheaper without sacrificing quality, and sustaining a strong, positive narrative about the benefits of rural education.

Second, we need to grow efforts aimed at upskilling under-certified educators and staff filling vacant positions in school districts. The risks of under-certified staff outlined above should not be understood as a reprimand. Rather, these are individuals with skills and passion, and they are an incredible asset already in place. We should be doing more to support efforts aimed at helping these individuals navigate the next steps into becoming full educators quickly and easily.

Third, we must develop a good method for managing geography. At the state level, we need to advocate for rural equity in funding mechanisms to ensure rural districts can provide adequate services to students and staff. We also need to ensure our mandated curriculum and content allows for flexible adaptation to local needs and realities without sacrificing learning outcomes. We also must go to better lengths to destigmatize and demystify living and working in a rural place. We cannot solve physical distances, but we can do a much better job of helping new and potential hires understand how to access desired goods and services; build connections in a remote place; and cultivate the senses of belonging and creative freedom that define the joys of educating in a rural school.

[1] AIRSS defines “rural” as both the 30s (Town) and 40s (Rural) locale codes of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). There is no single definition for “rural” in Illinois or within ISBE currently.

[2] Showalter, D., Hartman, S.L., Eppley, K., Johnson, J., & Klein, R. (2023).

Why Rural Matters 2023: Centering Equity and Opportunity, pgs. 6 & 105. National Rural Education Association.

[3] Glasgow, J. (2024). Growing Rural IL Success through CTE Programs, pg. 50. Association of Illinois Rural and Small Schools.